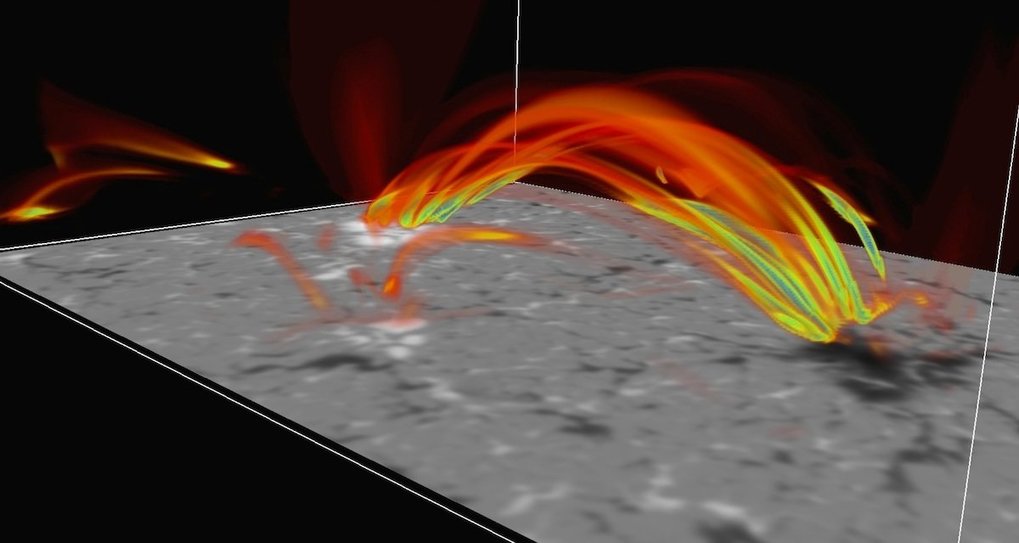

On the other hand, she finds this new uncertainty exciting. Astronomers will need to develop a way to observe the veil and confirm its existence, she says. Why? Her team’s new findings cast doubt on what solar scientists had thought they understood. “On one hand, this is depressing,” Malanushenko says. It’s also not clear how the apparent coronal veil might impact previous analyses of the sun’s atmosphere. “And we absolutely need to,” she says, to understand the sun’s atmosphere. “We don’t know which ones are real and which ones are not,” Malanushenko says. Still, not all coronal loops are necessarily ghosts within a coronal veil. It has complicated boundaries and a ragged structure. “The traditional thought was that if we see this arching coronal loop that there is a garden hose–like strand of plasma.” But the computer analysis now suggests the plasma’s structure is much more complex. The observations were mind-blowing, says Malanushenko. From certain viewing angles, what had been wrinkles now instead looked like coronal loops. The team changed the point of view by which the computer visualized these wrinkles in the modeled veil. They more closely resembled clouds of smoke. But these were neither thin nor as compact as had been expected. Plasma structures formed along the magnetic fields. The computer model suggested that many of the supposed coronal loops weren’t real. Parts of it folded in on itself like a wrinkled sheet. The plasma instead formed a curtainlike structure winding out from the sun’s surface. So the researchers expected to see neatly oriented strands of plasma.īut they didn’t.

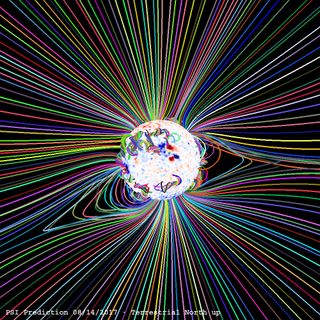

Coronal loops appear to align themselves to the sun’s magnetic field, like metal shavings around a bar magnet. That computer program had been developed to model the life cycle of a solar flare - powerful magnetic outbursts that shoot bright spurts of radiation into space.

She’s part of a team that tried to isolate individual coronal loops in 3-D computer simulations. Solar physicist Anna Malanushenko works at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. Astronomers also have puzzled over why the loops appear to be so orderly when they rise from the sun’s turbulent surface. In fact, coronal loops may be key to figuring out why the sun’s atmosphere is so much hotter than its surface. Its loops have been used to measure many of the corona’s traits, including its temperature and density. Only in the past few years have cientists begun to develop a better understanding of the sun’s complex corona. This astrophysicist works at Lockheed Martin’s Solar & Astrophysics Lab in Palo Alto, Calif. These loops, he says, “are so different than what we anticipated.” Aschwanden was not involved in the study. “It’s kind of inspiring to see these detailed structures,” says Markus Aschwanden. If true, these ghostly loops may change how scientists go about measuring some properties of our star. Researchers proposed these phantom loops March 2 in The Astrophysical Journal. Those computer programs were designed to simulate the sun’s atmosphere - including its outermost region, the corona. They base this idea on unexpected structures that emerged in computer models. Some, they say, might be an illusion created by dense “wrinkles” in a curtain of plasma known as the coronal veil. But many of the loops we see might not actually be there, scientists now report. These iconic features are known as coronal loops. Hot strands of plasma arch out from the sun’s surface.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)